Known in English as Baragaki: Unbroken Samurai, this film’s release was delayed from its initially scheduled date for May 2020 and is set to come to theaters October 15, 2021. In promotion for the film, a special video was aired 3 days ago on August 18th that focuses on understanding the history of the Shinsengumi which I have translated and subtitled.

Continue reading 燃えよ剣 – Moeyo Ken – Baragaki: Unbroken SamuraiTag Archives: japanese history

PAPER: Living Wood and Still Bodies

Written in December 2014 Wrote this after studying the Bunraku and Kabuki theaters, specifically the relationship of influence each theater form has (or had) on the other, from a historical, aesthetic, and performative context.

Living Wood and Still Bodies: Analyzing the Relationship Between Bunraku and Kabuki

When considering the variety of theatre the world has to offer, few have such spectacular a tradition or are as recognizable as the Kabuki and Bunraku theatres of Japan. While historically the two art forms were highly competitive with one another, scholars have argued for one art form being the more or less direct influence of the other for years. Upon studying the historical factors, visual aesthetics, and movement styles of both forms, however, it becomes apparent that discussion of this topic cannot be as clear cut and dry as some of these scholars make it out to be. Continue reading PAPER: Living Wood and Still Bodies

Women of the Floating World: Shizuka Gozen

The Dancing Women of Kyoto

Even at the height of Heian promiscuity, when noblemen had no problem finding a companion for the night and flitted merrily from one woman’s chamber to another, there were also prostitutes who offered a different sort of pleasure.

At one end of the scale were ordinary prostitutes who wandered the streets, waterways, hills, and woods and were referred to as “wandering women,” “floating women,” or “play women”.

At the other extreme were cultivated, refined professionals whom in English we might call courtesans. Some were of good family, fallen upon hard times. Others were noted for their beauty, brilliance, or talent. Skilled musicians, dancers, and singers, they were often the invited guests and chosen companions of the aristocrats. These high-class courtesans were the original precursors of the geisha and the oiran.

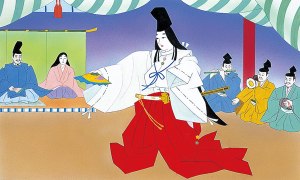

The most popular of these courtesans were the shirabyoshi (“white rhythm”) dancing women. To heighten their allure, they cross-dressed in white male clothing and manly court caps. They carried swords like men and performed highly charged erotic songs and dances to music with a rhythmic beat. Like the supermodels and rock singers of today, they were stars and the chosen companions of the country’s most powerful men.

The most popular of these courtesans were the shirabyoshi (“white rhythm”) dancing women. To heighten their allure, they cross-dressed in white male clothing and manly court caps. They carried swords like men and performed highly charged erotic songs and dances to music with a rhythmic beat. Like the supermodels and rock singers of today, they were stars and the chosen companions of the country’s most powerful men.

The Last Dance of Shizuka Gozen

The most celebrated of all shirabyoshi was Shizuka Gozen, the concubine of the 12th century legendary hero Minamoto no  Yoshitsune. She was renowned throughout the country for extraordinary beauty and also for the power of her dancing. In Japan, dance began as a way of supplicating the gods, (but eventually transformed in later times to be equated with prostitution) and once, when the country had been suffering from drought for a hundred days, the gods responded by sending rain as soon as Shizuka began to dance – or so goes the legend. Centuries later, when the geisha first appeared, they would claim Shizuka Gozen as their ancestor.

Yoshitsune. She was renowned throughout the country for extraordinary beauty and also for the power of her dancing. In Japan, dance began as a way of supplicating the gods, (but eventually transformed in later times to be equated with prostitution) and once, when the country had been suffering from drought for a hundred days, the gods responded by sending rain as soon as Shizuka began to dance – or so goes the legend. Centuries later, when the geisha first appeared, they would claim Shizuka Gozen as their ancestor.

Like most women in Japanese literature, history, and legend, Shizuka Gozen’s story is famous because of how that story ended. In 1185, when her lover, Minamoto no Yoshitsune, was forced to flee Kyoto and escape from his older brother and the new Shogun, Yoritomo, Shizuka Gozen accompanied him. However, Yoshitsune eventually sent her and the rest of his entourage back as it was only slowing him down.

Soon after Shizuka was captured and brought before Yoritomo. There she was interrogated as to Yoshitsune’s whereabouts. But, being plucky as well as beautiful – characteristics which would come to distinguish the geisha too – she refused to give anything away.

Yoritomo then forced her to dance for him, intending to intimidate and frighten the 18-year-old girl. But Shizuka did not flinch. Instead, she danced and sang a song full of praise for her lover, Yoshitsune, and longing to be at his side. This greatly angered Yoritomo, and he intended on having her put to death, but his wife, sympathetic to the young woman, begged for Shizuka’s life. With her help, Shizuka Gozen was finally released.

However, by this point it became apparent that Shizuka was pregnant with Yoshitsune’s child. Yoritomo declared that if it were a daughter she could live on peacefully, but if it were a son, he would have the child killed. Months later, she gave birth to a son, but again Yoritomo’s wife intervened and the child was spared but sent away to live with Shizuka’s mother.

Free to do as she pleased, Shizuka sought to follow her lover once more, but upon hearing of his death, she became a nun in Kyoto and died of grief. According to some tales, however, Shizuka was later killed along with her and Yoshitsune’s child, a son, by the order of Yoritomo.

Both the song and dance of Shizuka Gozen are famous, and are still performed to this day by geisha and actress alike.

Women of the Floating World: Ono no Komachi

Kyoto, the City of Love and Beauty

Long before women like the geisha or the oiran (courtesans) existed, Kyoto was the center of an extraordinarily effete, decadent, and promiscuous culture which transformed love into an art form and beauty into a cult.

Back then its name was not Kyoto, but Heian-Kyo, the “City of Peace and Tranquility.” Poets called it the “City of Purple Hills and Crystal Streams.” Under the rule of the emperor and his all-powerful ministers of state, the Fujiwara family, the country enjoyed three centuries of peace and prosperity that would later be called the Heian Period (794-1195).

For the aristocrats of the Heian court, it was a time of unending leisure which they filled with the pursuit of art and beauty. They spent their days holding moon-viewing parties, mixing incense, writing poems, and playing the game of love.

Promiscuity was the norm. Following the Confucian precepts which governed society, marriage was a purely political affair arranged by the parents to create an advantageous alliance between families. Love and marriage had nothing to do with each other. In fact, a court lady was more likely to suffer censure for a lapse of taste in the colors of her robes than for her numerous lovers. Centuries later, when pleasure quarters were built where men could transcend their everyday lives and imagine themselves noblemen of leisure, the oiran and geisha modeled the dreams they sold after the romantic culture of the Heian court.

But what made the Heian period most extraordinary was the way art and the cult of beauty were bound up with love. More than sexual desire or gut-wrenching passion, love was an art form, an opportunity to put brush to paper, to immortalize the moment in a small literary gem.

But what made the Heian period most extraordinary was the way art and the cult of beauty were bound up with love. More than sexual desire or gut-wrenching passion, love was an art form, an opportunity to put brush to paper, to immortalize the moment in a small literary gem.

When a nobleman caught wind that a certain lady was very beautiful or, even more enticing, had beautiful handwriting, he would sit down to compose a waka poem and brush it, in his finest calligraphy, on delicately hued scented paper. This was how he first began courting. And when the lady received it, she would assess the handwriting and color of the paper, as well as the wit and appropriateness of the poem, before brushing a reply. If she deemed him unworthy, she would refrain from writing a reply and that would be the end of the affair. The nobleman in turn would be waiting with bated breath to see whether her handwriting and poem lived up to expectations. If the exchange of poems was satisfactory, he would eventually pay her a visit.

Ono no Komachi’s Deadly Beauty

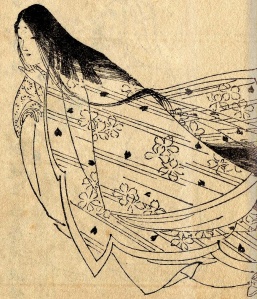

The most famous of all Heian beauties was Ono no Komachi, a lady-in-waiting in the imperial court. So beautiful, proud, and  passionate was she that she has never been forgotten. Her name has come down through the ages as Japan’s all-time femme fatale, and has been many a geisha and oiran’s model woman.

passionate was she that she has never been forgotten. Her name has come down through the ages as Japan’s all-time femme fatale, and has been many a geisha and oiran’s model woman.

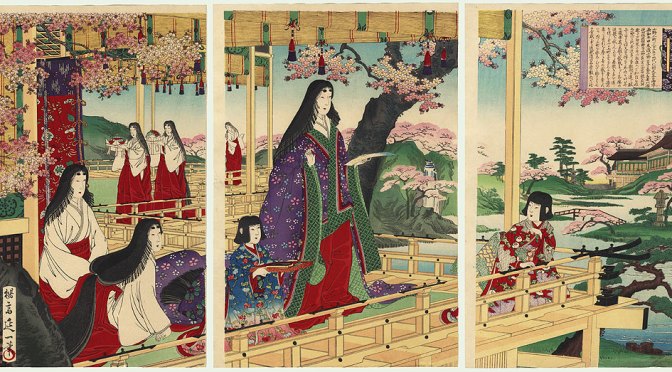

As is told in Noh plays and legend, with her silken raven tresses falling to the floor in cascades, a face like a blossom, and eyebrows painted as perfect crescent moons, she drove the noblemen of her day mad with desire. But she was not just a pretty face. She was brilliant, accomplished, powerful, and tough-minded, a woman of burning passions which she wrote about in waka poems that continue to be read and loved to this day.

Unlike the maidens of medieval Europe waiting passively for a knight in shining armor to come courting, however, Ono no Komachi herself burned with fiery passion. She would only yield to a man who could prove himself worthy of her, and she made a reputation for herself by posing great challenges for potential lovers.

For the most forlorn of all, a commander of the imperial guard named Fukakusa no Shii no Shosho, she devised the cruelest of ordeals: He was to come to her house for a hundred nights and sleep outside on a bench used to support the shafts of her chariot before she would even consider his proposal. After persevering for ninety-nine days and on the joyful day when he was to be rewarded for all his efforts, Captain Shosho suddenly died – from heartbreak, perhaps, or from exposure.

For such hard-heartedness, Komachi suffered the cruelest punishment of all – the loss of her beauty. Instead of dying young, like Cleopatra or Helen of Troy and leaving a beautiful memory, she lived to be a hundred years old. And after the death of Captain Shosho, she was spurned and driven from court. In the end she died a tattered, crazed beggar woman.

For such hard-heartedness, Komachi suffered the cruelest punishment of all – the loss of her beauty. Instead of dying young, like Cleopatra or Helen of Troy and leaving a beautiful memory, she lived to be a hundred years old. And after the death of Captain Shosho, she was spurned and driven from court. In the end she died a tattered, crazed beggar woman.

Like the renowned cherry blossoms, beauty is all too fleeting. This is  what gives Ono no Komachi’s story its poignancy. The beauty of women can drive men to distraction and to their deaths but in the end men get their revenge: such women die old and alone. Komachi’s tragic end made her all the more the perfect precursor of the geisha and the oiran, for like Ono no Komachi, they too came to be regarded with ambivalence. They were sirens, so beautiful that men could not resist them – yet to yield and fall in love with one was to court disaster.

what gives Ono no Komachi’s story its poignancy. The beauty of women can drive men to distraction and to their deaths but in the end men get their revenge: such women die old and alone. Komachi’s tragic end made her all the more the perfect precursor of the geisha and the oiran, for like Ono no Komachi, they too came to be regarded with ambivalence. They were sirens, so beautiful that men could not resist them – yet to yield and fall in love with one was to court disaster.

PAPER: She’s the Man

Written in May 2011 Wrote this after studying Kabuki and Takarazuka theaters and their unique acting roles, namely the onnagata and otokoyaku, and the interpretations of gender through their performances.

She’s the Man: Performing Gender in Kabuki and Takarazuka through Kata

Of all the theatre forms in the world, there are few as mystifying and fascinating as those found in Japan, especially the highly stylized Kabuki and Takarazuka. What is it about the Kabuki and Takarazuka aesthetics that attract their respective audiences? More than the music, the dancing, the romance, or the lavish spectacle, it is the male-role specializing otokoyaku in the all-female Takarazuka theatre and the female-role specializing onnagata in the all-male Kabuki theatre that draws spectators. Both of these actors demonstrate that gender is not connected to one’s sex, but is a performance. A performance which requires the learning of a highly stylized set of patterns known as kata, by which the onnagata in Kabuki and the otokoyaku in Takarazuka learn to exude femininity and masculinity respectively, as well as become more elegant, graceful, and attractive than a “real” woman or man ever could. This in turn affects the audience’s perception of gender for both male and female spectators and demonstrates the cultural difference between Japan and the West when defining “femininity” and “masculinity.” Continue reading PAPER: She’s the Man

PAPER: Through the Eyes of the Fox

Written in May 2009 I wrote this paper based on my research on Shinto (sp. Inari) and East Asian folklore regarding the fox. I was fascinated by Fushimi Inari Taisha, and I was familiar with the kitsune as well as Shinto, so I started researching Inari and fox lore in more detail.

Through the Eyes of the Fox: Japan’s Connections with Korea through Inari Worship and the Plausible Influence on Shinto Religion

As the sunlight fades and dusk creeps in, an air of eerie tranquility settles on the shrine complex. Passing underneath thousands of vermillion torii gates, it seems like a tunnel leading to another world. And everywhere one looks there is the expectation for a slender, lithe vulpine creature with a luxurious tail to suddenly appear and lope through the trees. Such is the atmosphere at Fushimi Inari Taisha, the head shrine of Inari, one of Shinto’s most diverse and popular kami. One of the most unique aspects of Inari worship that is often overlooked is its strong connections to the Korean peninsula, which are most distinctly seen in its origins and the central symbol of Inari, the fox. Given how prominent Inari worship is, how the Korean impact on it may have influenced Shinto beliefs in general is also worth examining. Continue reading PAPER: Through the Eyes of the Fox