Kyoto, the City of Love and Beauty

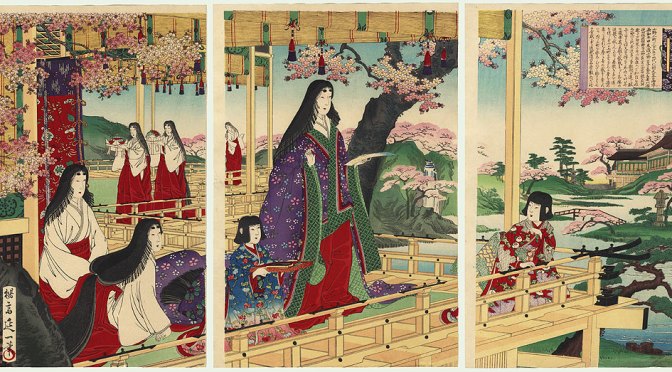

Long before women like the geisha or the oiran (courtesans) existed, Kyoto was the center of an extraordinarily effete, decadent, and promiscuous culture which transformed love into an art form and beauty into a cult.

Back then its name was not Kyoto, but Heian-Kyo, the “City of Peace and Tranquility.” Poets called it the “City of Purple Hills and Crystal Streams.” Under the rule of the emperor and his all-powerful ministers of state, the Fujiwara family, the country enjoyed three centuries of peace and prosperity that would later be called the Heian Period (794-1195).

For the aristocrats of the Heian court, it was a time of unending leisure which they filled with the pursuit of art and beauty. They spent their days holding moon-viewing parties, mixing incense, writing poems, and playing the game of love.

Promiscuity was the norm. Following the Confucian precepts which governed society, marriage was a purely political affair arranged by the parents to create an advantageous alliance between families. Love and marriage had nothing to do with each other. In fact, a court lady was more likely to suffer censure for a lapse of taste in the colors of her robes than for her numerous lovers. Centuries later, when pleasure quarters were built where men could transcend their everyday lives and imagine themselves noblemen of leisure, the oiran and geisha modeled the dreams they sold after the romantic culture of the Heian court.

But what made the Heian period most extraordinary was the way art and the cult of beauty were bound up with love. More than sexual desire or gut-wrenching passion, love was an art form, an opportunity to put brush to paper, to immortalize the moment in a small literary gem.

But what made the Heian period most extraordinary was the way art and the cult of beauty were bound up with love. More than sexual desire or gut-wrenching passion, love was an art form, an opportunity to put brush to paper, to immortalize the moment in a small literary gem.

When a nobleman caught wind that a certain lady was very beautiful or, even more enticing, had beautiful handwriting, he would sit down to compose a waka poem and brush it, in his finest calligraphy, on delicately hued scented paper. This was how he first began courting. And when the lady received it, she would assess the handwriting and color of the paper, as well as the wit and appropriateness of the poem, before brushing a reply. If she deemed him unworthy, she would refrain from writing a reply and that would be the end of the affair. The nobleman in turn would be waiting with bated breath to see whether her handwriting and poem lived up to expectations. If the exchange of poems was satisfactory, he would eventually pay her a visit.

Ono no Komachi’s Deadly Beauty

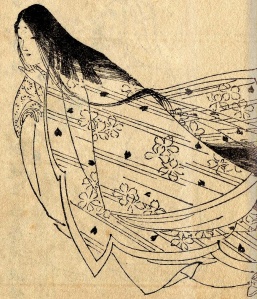

The most famous of all Heian beauties was Ono no Komachi, a lady-in-waiting in the imperial court. So beautiful, proud, and  passionate was she that she has never been forgotten. Her name has come down through the ages as Japan’s all-time femme fatale, and has been many a geisha and oiran’s model woman.

passionate was she that she has never been forgotten. Her name has come down through the ages as Japan’s all-time femme fatale, and has been many a geisha and oiran’s model woman.

As is told in Noh plays and legend, with her silken raven tresses falling to the floor in cascades, a face like a blossom, and eyebrows painted as perfect crescent moons, she drove the noblemen of her day mad with desire. But she was not just a pretty face. She was brilliant, accomplished, powerful, and tough-minded, a woman of burning passions which she wrote about in waka poems that continue to be read and loved to this day.

Unlike the maidens of medieval Europe waiting passively for a knight in shining armor to come courting, however, Ono no Komachi herself burned with fiery passion. She would only yield to a man who could prove himself worthy of her, and she made a reputation for herself by posing great challenges for potential lovers.

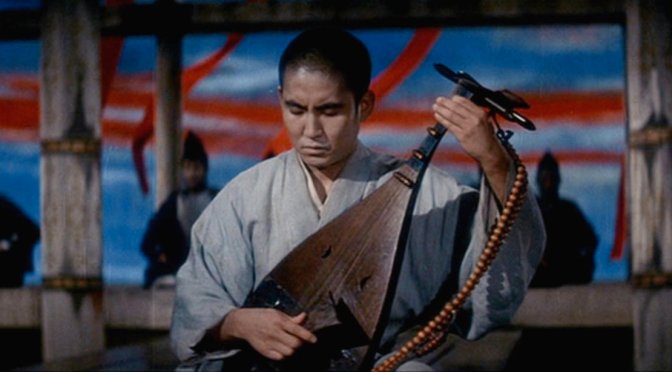

For the most forlorn of all, a commander of the imperial guard named Fukakusa no Shii no Shosho, she devised the cruelest of ordeals: He was to come to her house for a hundred nights and sleep outside on a bench used to support the shafts of her chariot before she would even consider his proposal. After persevering for ninety-nine days and on the joyful day when he was to be rewarded for all his efforts, Captain Shosho suddenly died – from heartbreak, perhaps, or from exposure.

For such hard-heartedness, Komachi suffered the cruelest punishment of all – the loss of her beauty. Instead of dying young, like Cleopatra or Helen of Troy and leaving a beautiful memory, she lived to be a hundred years old. And after the death of Captain Shosho, she was spurned and driven from court. In the end she died a tattered, crazed beggar woman.

For such hard-heartedness, Komachi suffered the cruelest punishment of all – the loss of her beauty. Instead of dying young, like Cleopatra or Helen of Troy and leaving a beautiful memory, she lived to be a hundred years old. And after the death of Captain Shosho, she was spurned and driven from court. In the end she died a tattered, crazed beggar woman.

Like the renowned cherry blossoms, beauty is all too fleeting. This is  what gives Ono no Komachi’s story its poignancy. The beauty of women can drive men to distraction and to their deaths but in the end men get their revenge: such women die old and alone. Komachi’s tragic end made her all the more the perfect precursor of the geisha and the oiran, for like Ono no Komachi, they too came to be regarded with ambivalence. They were sirens, so beautiful that men could not resist them – yet to yield and fall in love with one was to court disaster.

what gives Ono no Komachi’s story its poignancy. The beauty of women can drive men to distraction and to their deaths but in the end men get their revenge: such women die old and alone. Komachi’s tragic end made her all the more the perfect precursor of the geisha and the oiran, for like Ono no Komachi, they too came to be regarded with ambivalence. They were sirens, so beautiful that men could not resist them – yet to yield and fall in love with one was to court disaster.