The Dancing Women of Kyoto

Even at the height of Heian promiscuity, when noblemen had no problem finding a companion for the night and flitted merrily from one woman’s chamber to another, there were also prostitutes who offered a different sort of pleasure.

At one end of the scale were ordinary prostitutes who wandered the streets, waterways, hills, and woods and were referred to as “wandering women,” “floating women,” or “play women”.

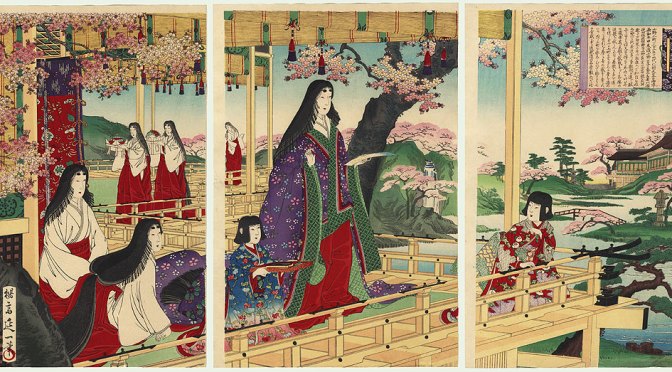

At the other extreme were cultivated, refined professionals whom in English we might call courtesans. Some were of good family, fallen upon hard times. Others were noted for their beauty, brilliance, or talent. Skilled musicians, dancers, and singers, they were often the invited guests and chosen companions of the aristocrats. These high-class courtesans were the original precursors of the geisha and the oiran.

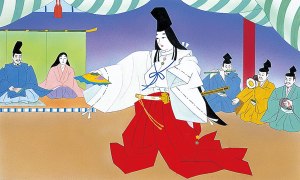

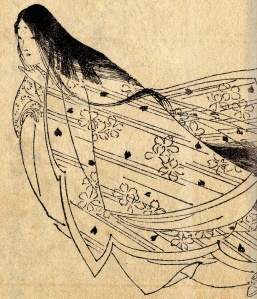

The most popular of these courtesans were the shirabyoshi (“white rhythm”) dancing women. To heighten their allure, they cross-dressed in white male clothing and manly court caps. They carried swords like men and performed highly charged erotic songs and dances to music with a rhythmic beat. Like the supermodels and rock singers of today, they were stars and the chosen companions of the country’s most powerful men.

The most popular of these courtesans were the shirabyoshi (“white rhythm”) dancing women. To heighten their allure, they cross-dressed in white male clothing and manly court caps. They carried swords like men and performed highly charged erotic songs and dances to music with a rhythmic beat. Like the supermodels and rock singers of today, they were stars and the chosen companions of the country’s most powerful men.

The Last Dance of Shizuka Gozen

The most celebrated of all shirabyoshi was Shizuka Gozen, the concubine of the 12th century legendary hero Minamoto no  Yoshitsune. She was renowned throughout the country for extraordinary beauty and also for the power of her dancing. In Japan, dance began as a way of supplicating the gods, (but eventually transformed in later times to be equated with prostitution) and once, when the country had been suffering from drought for a hundred days, the gods responded by sending rain as soon as Shizuka began to dance – or so goes the legend. Centuries later, when the geisha first appeared, they would claim Shizuka Gozen as their ancestor.

Yoshitsune. She was renowned throughout the country for extraordinary beauty and also for the power of her dancing. In Japan, dance began as a way of supplicating the gods, (but eventually transformed in later times to be equated with prostitution) and once, when the country had been suffering from drought for a hundred days, the gods responded by sending rain as soon as Shizuka began to dance – or so goes the legend. Centuries later, when the geisha first appeared, they would claim Shizuka Gozen as their ancestor.

Like most women in Japanese literature, history, and legend, Shizuka Gozen’s story is famous because of how that story ended. In 1185, when her lover, Minamoto no Yoshitsune, was forced to flee Kyoto and escape from his older brother and the new Shogun, Yoritomo, Shizuka Gozen accompanied him. However, Yoshitsune eventually sent her and the rest of his entourage back as it was only slowing him down.

Soon after Shizuka was captured and brought before Yoritomo. There she was interrogated as to Yoshitsune’s whereabouts. But, being plucky as well as beautiful – characteristics which would come to distinguish the geisha too – she refused to give anything away.

Yoritomo then forced her to dance for him, intending to intimidate and frighten the 18-year-old girl. But Shizuka did not flinch. Instead, she danced and sang a song full of praise for her lover, Yoshitsune, and longing to be at his side. This greatly angered Yoritomo, and he intended on having her put to death, but his wife, sympathetic to the young woman, begged for Shizuka’s life. With her help, Shizuka Gozen was finally released.

However, by this point it became apparent that Shizuka was pregnant with Yoshitsune’s child. Yoritomo declared that if it were a daughter she could live on peacefully, but if it were a son, he would have the child killed. Months later, she gave birth to a son, but again Yoritomo’s wife intervened and the child was spared but sent away to live with Shizuka’s mother.

Free to do as she pleased, Shizuka sought to follow her lover once more, but upon hearing of his death, she became a nun in Kyoto and died of grief. According to some tales, however, Shizuka was later killed along with her and Yoshitsune’s child, a son, by the order of Yoritomo.

Both the song and dance of Shizuka Gozen are famous, and are still performed to this day by geisha and actress alike.