According to the Chinese lunar calendar, this year today, September 2nd, marks the end of the month of guǐ yuè (鬼月) or Ghost Month. While the 15th day of the month or Hungry Ghost Festival is considered to be the most important of times, the last day of the seventh month in the Chinese lunar calendar is also significant as it is when the doors to the underworld are closed once again, and the roaming spirits who have come to visit are sent back from whence they came.

Sending Back Spirits at the End of Ghost Month

Traditionally, Taoist priests would perform chants to announce to the spirits that it was time for their return to the underworld, known as yīnjiān (陰間) or literally the “moon or hidden/shaded place”, and to drive them out from the world of the living, known in Taoism as yángjiān (陽間) or literally the “sun or open place” with the sound of their chanting. What is perhaps more familiar and common nowadays, however, is the lighting of lanterns, typically lotus-shaped, and floating them on lakes or rivers to guide those visiting spirits back to the underworld. Families will often write the names of ancestors believed to be visiting them on their lanterns to ensure they will be followed back. Many will burn further offerings fashioned out of joss paper such as money or other material possessions for ancestral spirits to take with them.

Aside from the lanterns floated explicitly for ancestral spirits, additional lanterns are made for any wandering ghosts, including those whose grievances were so strong that their souls were trapped in the world of the living, in hopes of guiding them to where they can be at peace. Despite one’s best efforts, however, some ghosts never make it back and remain in the world of the living, even well after the end of Ghost Month.

Ghosts Who Stay in the World of the Living

As has been mentioned in earlier posts, the word guǐ (鬼) is the general term to refer to “ghosts” in Chinese, but it can also be used to mean a monster equivalent to a “demon”. There are quite literally dozens of different kinds of guǐ recorded, and out of the many types of ghosts and apparitions known to exist in Chinese folklore, there are certain guǐ that are considered more important and also most likely encountered by the living, both during and outside of Ghost Month.

The first is the è guǐ (餓鬼) or “hungry ghost” which serves as the basis for many of the traditions practiced during the Hungry Ghost Festival. According to Buddhism, an è guǐ is the ghost of a person who always wanted more than they had and who was never grateful for what they had or was given. So now in death, these “hungry ghosts” cannot find peace as ghosts any more than they could while they were alive. It is said that as punishment, no amount of food can fully satisfy their hunger, though that does not stop them from seeking out the living for help. Anyone who refuses to feed an è guǐ runs the risk of being cursed and bringing disaster to both their home and loved ones.

Another type of ghost who often remains in the world of the living is the yuān guǐ (冤鬼), literally “ghost with a grievance.” These are vengeful ghosts of those who died wrongful deaths, who cannot rest in peace and thus cannot be reincarnated according to Buddhism. As a result, they stay and are driven to approach or seek out living humans who can help them get justice so they can pass on to the underworld.

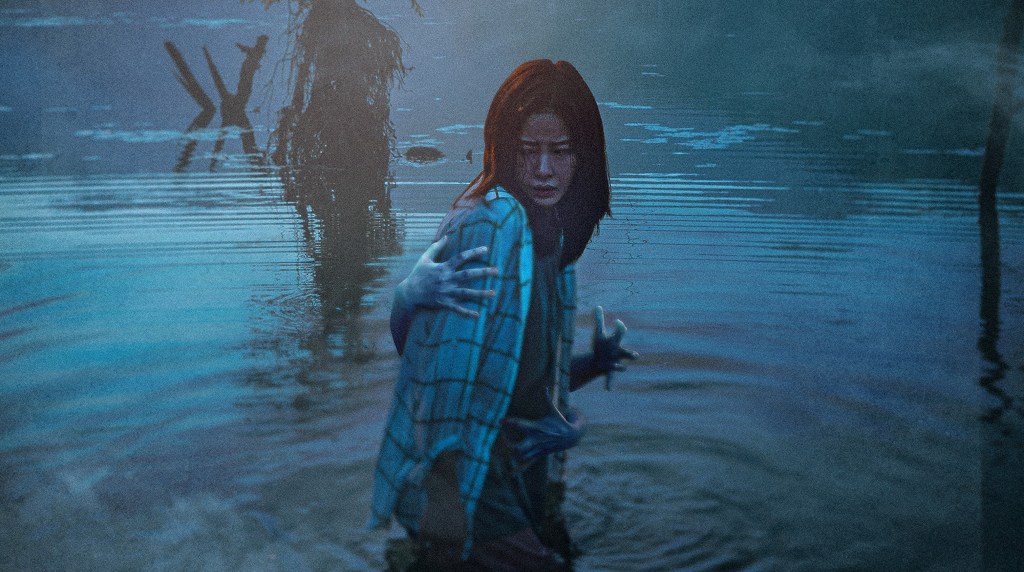

As a special subcategory of ghosts who have suffered wrongful or abnormal deaths, there are those who are unable to make their way to the underworld due to having died drowning. According to Chinese folklore it is believed that a person who has drowned is trapped in the world of the living, forced to haunt whatever body of water they died in. They become what is commonly known as a shuǐ guǐ (水鬼), or “water ghost” and considered by many to be the type of guǐ the living is most likely to encounter throughout the year if they go near a body of water such as the river or ocean. It is for this reason that many people insist on wearing talismans or amulets whenever they go swimming or just go near water, even outside of (but especially during) Ghost Month.

In comparison to the hungry, vengeful, or watery, there are also those who have no sense of purpose whatsoever. Referred collectively as yóu hún yě guǐ (游魂野鬼), literally “wandering souls and wild ghosts”, these ghosts are fated to endlessly roam the world of the living, never passing onto the underworld. This is largely due to the fact that these “wandering ghosts” are of people who have no living relatives to care for their souls. Alternatively (or additionally), they are forced to wander because their body was never properly laid to rest.

Some of the most dangerous or deadly and ever-present guǐ in Chinese folklore, however, are believed to be those that live within the human body. For example, the fù guǐ (腹鬼) or “stomach ghost” is said to live in the abdomen (as its name suggests), whispering things to their victim(s) that only they can hear and causing them extreme pain in their internal organs. This pain is centered mainly on the stomach and typically followed by death.

Similar to the fù guǐ is the gāohuāng guǐ (膏肓鬼), literally “vital organs ghost”, which is said to live in the area between the heart and the diaphragm (some say the throat). It is believed that this ghost is responsible for inspiring “dark” thoughts that often manifest as a physical, unexplained and usually fatal illness in the living. The existence of this type of ghost is considered to be the origins for the Chinese idiom xīn zhōng yǒu guǐ (心中有鬼), which literally translates as “to have a demon in one’s heart” and is used to refer to when someone has something to hide (as in a guilt conscience) and/or harbors ulterior motives.

For both the fù guǐ and the gāohuāng guǐ, their victims are rarely known to survive, making them some of the most frightening in compendiums of Chinese folklore. This is particularly because due to their residing inside the human body, it is unknown what brings about their existence or what they even look like,